Typhoid fever

Typhoid fever

| Typhoid fever | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Slow fever, typhoid |

| Rose spots on the chest of a person with typhoid fever | |

| Specialty | Infectious disease |

| Symptoms | Fever, abdominal pain, headache, rash[1] |

| Usual onset | 6–30 days after exposure[1][2] |

| Causes | Salmonella enterica subsp. enterica (spread by food or water contaminated with feces)[3][4] |

| Risk factors | Poor sanitation, poor hygiene.[3] |

| Diagnostic method | Bacterial culture, DNA detection[2][3][5] |

| Differential diagnosis | Other infectious diseases[6] |

| Prevention | Typhoid vaccine, handwashing[2][7] |

| Treatment | Antibiotics[3] |

| Frequency | 12.5 million (2015)[8] |

| Deaths | 149,000 (2015)[9] |

Video summary (script)

Typhoid fever, also known simply as typhoid, is a bacterial infection due to a specific type of Salmonella that causes symptoms.[3] Symptoms may vary from mild to severe, and usually begin 6 to 30 days after exposure.[1][2] Often there is a gradual onset of a high fever over several days.[1] This is commonly accompanied by weakness, abdominal pain, constipation, headaches, and mild vomiting.[2][6] Some people develop a skin rash with rose colored spots.[2] In severe cases, people may experience confusion.[6] Without treatment, symptoms may last weeks or months.[2] Diarrhea is uncommon.[6] Other people may carry the bacterium without being affected; however, they are still able to spread the disease to others.[4] Typhoid fever is a type of enteric fever, along with paratyphoid fever.[3]

The cause is the bacterium Salmonella enterica subsp. enterica growing in the intestines and blood.[2][6] Typhoid is spread by eating or drinking food or water contaminated with the feces of an infected person.[4] Risk factors include poor sanitation and poor hygiene.[3] Those who travel in the developing world are also at risk.[6] Only humans can be infected.[4] Symptoms are similar to those of many other infectious diseases.[6] Diagnosis is by either culturing the bacteria or detecting their DNA in the blood, stool, or bone marrow.[2][3][5] Culturing the bacterium can be difficult.[10] Bone-marrow testing is the most accurate.[5]

A typhoid vaccine can prevent about 40 to 90% of cases during the first two years.[7] The vaccine may have some effect for up to seven years.[3] For those at high risk or people traveling to areas where the disease is common, vaccination is recommended.[4] Other efforts to prevent the disease include providing clean drinking water, good sanitation, and handwashing.[2][4] Until an individual's infection is confirmed as cleared, the individual should not prepare food for others.[2] The disease is treated with antibiotics such as azithromycin, fluoroquinolones, or third-generation cephalosporins.[3] Resistance to these antibiotics has been developing, which has made treatment of the disease more difficult.[3][11]

In 2015, 12.5 million new cases worldwide were reported.[8] The disease is most common in India.[3] Children are most commonly affected.[3][4] Rates of disease decreased in the developed world in the 1940s as a result of improved sanitation and use of antibiotics to treat the disease.[4] Each year in the United States, about 400 cases are reported and the disease occurs in an estimated 6,000 people.[6][12] In 2015, it resulted in about 149,000 deaths worldwide – down from 181,000 in 1990 (about 0.3% of the global total).[9][13] The risk of death may be as high as 20% without treatment.[4] With treatment, it is between 1 and 4%.[3][4] Typhus is a different disease.[14] However, the name typhoid means "resembling typhus" due to the similarity in symptoms.[15]

| Typhoid fever | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Slow fever, typhoid |

| Rose spots on the chest of a person with typhoid fever | |

| Specialty | Infectious disease |

| Symptoms | Fever, abdominal pain, headache, rash[1] |

| Usual onset | 6–30 days after exposure[1][2] |

| Causes | Salmonella enterica subsp. enterica (spread by food or water contaminated with feces)[3][4] |

| Risk factors | Poor sanitation, poor hygiene.[3] |

| Diagnostic method | Bacterial culture, DNA detection[2][3][5] |

| Differential diagnosis | Other infectious diseases[6] |

| Prevention | Typhoid vaccine, handwashing[2][7] |

| Treatment | Antibiotics[3] |

| Frequency | 12.5 million (2015)[8] |

| Deaths | 149,000 (2015)[9] |

Signs and symptoms

Rose spots on chest of a person with typhoid fever

Classically, the progression of untreated typhoid fever is divided into four distinct stages, each lasting about a week. Over the course of these stages, the patient becomes exhausted and emaciated.[16]

In the first week, the body temperature rises slowly, and fever fluctuations are seen with relative bradycardia (Faget sign), malaise, headache, and cough. A bloody nose (epistaxis) is seen in a quarter of cases, and abdominal pain is also possible. A decrease in the number of circulating white blood cells (leukopenia) occurs with eosinopenia and relative lymphocytosis; blood cultures are positive for Salmonella enterica subsp. enterica or S. paratyphi. The Widal test is usually negative in the first week.[17]

In the second week, the person is often too tired to get up, with high fever in plateau around 40 °C (104 °F) and bradycardia (sphygmothermic dissociation or Faget sign), classically with a dicrotic pulse wave. Delirium can occur, where the patient is often calm, but sometimes becomes agitated. This delirium has led to typhoid receiving the nickname "nervous fever". Rose spots appear on the lower chest and abdomen in around a third of patients. Rhonchi (rattling breathing sounds) are heard in the base of the lungs. The abdomen is distended and painful in the right lower quadrant, where a rumbling sound can be heard. Diarrhea can occur in this stage, but constipation is also common. The spleen and liver are enlarged (hepatosplenomegaly) and tender, and liver transaminases are elevated. The Widal test is strongly positive, with antiO and antiH antibodies. Blood cultures are sometimes still positive at this stage. The major symptom of this fever is that it usually rises in the afternoon up to the first and second week.

In the third week of typhoid fever, a number of complications can occur: Intestinal haemorrhage due to bleeding in congested Peyer's patches occurs; this can be very serious, but is usually not fatal. Intestinal perforation in the distal ileum is a very serious complication and is frequently fatal. It may occur without alarming symptoms until septicaemia or diffuse peritonitis sets in. Encephalitis Respiratory diseases such as pneumonia and acute bronchitis Neuropsychiatric symptoms (described as "muttering delirium" or "coma vigil"), with picking at bedclothes or imaginary objects Metastatic abscesses, cholecystitis, endocarditis, and osteitis The fever is still very high and oscillates very little over 24 hours. Dehydration ensues, and the patient is delirious (typhoid state). One-third of affected individuals develop a macular rash on the trunk. Platelet count goes down slowly and the risk of bleeding rises.

By the end of third week, the fever starts subsiding.

Causes

Bacteria

Transmission

Unlike other strains of Salmonella, no animal carriers of typhoid are known.[20] Humans are the only known carriers of the bacteria.[20] S. e. subsp. enterica is spread through the fecal-oral route from individuals who are currently infected and from asymptomatic carriers of the bacteria.[20] An asymptomatic human carrier is an individual who is still excreting typhoid bacteria in their stool a year after the acute stage of the infection.[20]

Diagnosis

Diagnosis is made by any blood, bone marrow, or stool cultures and with the Widal test (demonstration of antibodies against Salmonella antigens O-somatic and H-flagellar). In epidemics and less wealthy countries, after excluding malaria, dysentery, or pneumonia, a therapeutic trial time with chloramphenicol is generally undertaken while awaiting the results of the Widal test and cultures of the blood and stool.[21]

The Widal test is time-consuming and prone to significant false positive results. The test may also be falsely negative in the early course of illness. However, unlike the Typhidot test, the Widal test quantifies the specimen with titres.

Typhidot is a medical test consisting of a dot ELISA kit that detects IgM and IgG antibodies against the outer membrane protein (OMP) of the Salmonella enterica subsp. enterica. The typhidot test becomes positive within 2–3 days of infection and separately identifies IgM and IgG antibodies. The test is based on the presence of specific IgM and IgG antibodies to a specific 50Kd OMP antigen, which is impregnated on nitrocellulose strips. IgM shows recent infection whereas IgG signifies remote infection. The most important limitation of this test is that it is not quantitative and the result is only positive or negative.

Prevention

Doctor administering a typhoid vaccination at a school in San Augustine County, Texas, 1943

Sanitation and hygiene are important to prevent typhoid. It can only spread in environments where human feces are able to come into contact with food or drinking water. Careful food preparation and washing of hands are crucial to prevent typhoid. Industrialization, and in particular, the invention of the automobile, contributed greatly to the elimination of typhoid fever, as it eliminated the public-health hazards associated with having horse manure in public streets, which led to large number of flies,[22] which are known as vectors of many pathogens, including Salmonellaspp.[23] According to statistics from the United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the chlorination of drinking water has led to dramatic decreases in the transmission of typhoid fever in the United States.

Vaccination

Two typhoid vaccines are licensed for use for the prevention of typhoid:[7] the live, oral Ty21a vaccine (sold as Vivotif by Crucell Switzerland AG) and the injectable typhoid polysaccharide vaccine (sold as Typhim Vi by Sanofi Pasteur and Typherix by GlaxoSmithKline). Both are efficacious and recommended for travellers to areas where typhoid is endemic. Boosters are recommended every five years for the oral vaccine and every two years for the injectable form.[24] An older, killed whole-cell vaccine is still used in countries where the newer preparations are not available, but this vaccine is no longer recommended for use because it has a higher rate of side effects (mainly pain and inflammation at the site of the injection).[25]

To help decrease rates of typhoid fever in developing nations, the World Health Organization (WHO) endorsed the use of a vaccination program starting in 1999. Vaccinations have proven to be a great way at controlling outbreaks in high incidence areas. Just as important, it is also very cost-effective. Vaccination prices are normally low, less than US $1 per dose. Because the price is low, poverty-stricken communities are more willing to take advantage of the vaccinations.[26] Although vaccination programs for typhoid have proven to be effective, they alone cannot eliminate typhoid fever.[26] Combining the use of vaccines with increasing public health efforts is the only proven way to control this disease.[26]

Since the 1990s, two typhoid fever vaccines have been recommended by the WHO. The ViPS vaccine is given via injection, while the Ty21a is taken through capsules. Only people 2 years or older are recommended to be vaccinated with the ViPS vaccine, and it requires a revaccination after 2–3 years with a 55–72% vaccine efficacy. The alternative Ty21a vaccine is recommended for people 5 years or older, and has a 5-7-year duration with a 51–67% vaccine efficacy. The two different vaccines have been proven as a safe and effective treatment for epidemic disease control in multiple regions.[27]

A version combined with hepatitis A is also available.[28]

Treatment

Oral rehydration therapy

The rediscovery of oral rehydration therapy in the 1960s provided a simple way to prevent many of the deaths of diarrheal diseases in general.

Antibiotics

Typhoid fever, when properly treated, is not fatal in most cases. Antibiotics, such as ampicillin, chloramphenicol, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, amoxicillin, and ciprofloxacin, have been commonly used to treat typhoid fever.[37] Treatment of the disease with antibiotics reduces the case-fatality rate to about 1%.[38]

Without treatment, some patients develop sustained fever, bradycardia, hepatosplenomegaly, abdominal symptoms, and occasionally, pneumonia. In white-skinned patients, pink spots, which fade on pressure, appear on the skin of the trunk in up to 20% of cases. In the third week, untreated cases may develop gastrointestinal and cerebral complications, which may prove fatal in up to 10–20% of cases. The highest case fatality rates are reported in children under 4 years. Around 2–5% of those who contract typhoid fever become chronic carriers, as bacteria persist in the biliary tract after symptoms have resolved.[39]

Surgery

Surgery is usually indicated if intestinal perforation occurs. One study found a 30-day mortality rate of 9% (8/88), and surgical site infections at 67% (59/88), with the disease burden borne predominantly by low-resource countries.[40]

For surgical treatment, most surgeons prefer simple closure of the perforation with drainage of the peritoneum. Small-bowel resection is indicated for patients with multiple perforations. If antibiotic treatment fails to eradicate the hepatobiliary carriage, the gallbladder should be resected. Cholecystectomy is not always successful in eradicating the carrier state because of persisting hepatic infection.

Resistance

As resistance to ampicillin, chloramphenicol, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, and streptomycin is now common, these agents have not been used as first–line treatment of typhoid fever for almost 20 years. Typhoid resistant to these agents is known as multidrug-resistant typhoid.

Ciprofloxacin resistance is an increasing problem, especially in the Indian subcontinent and Southeast Asia. Many centres are shifting from using ciprofloxacin as the first line for treating suspected typhoid originating in South America, India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, Thailand, or Vietnam. For these people, the recommended first-line treatment is ceftriaxone. Also, azithromycin has been suggested to be better at treating resistant typhoid in populations than both fluoroquinolone drugs and ceftriaxone.[30] Azithromycin significantly reduces relapse rates compared with ceftriaxone.

A separate problem exists with laboratory testing for reduced susceptibility to ciprofloxacin; current recommendations are that isolates should be tested simultaneously against ciprofloxacin (CIP) and against nalidixic acid (NAL), and that isolates that are sensitive to both CIP and NAL should be reported as "sensitive to ciprofloxacin", but that isolates testing sensitive to CIP but not to NAL should be reported as "reduced sensitivity to ciprofloxacin". However, an analysis of 271 isolates showed that around 18% of isolates with a reduced susceptibility to ciprofloxacin (MIC 0.125–1.0 mg/l) would not be picked up by this method.[41] How this problem can be solved is not certain, because most laboratories around the world (including the West) are dependent on disk testing and cannot test for MICs.

Epidemiology

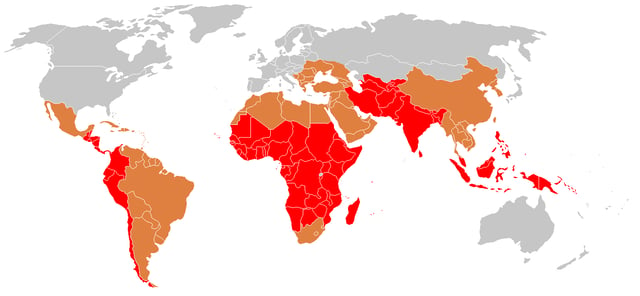

Incidence of typhoid fever♦ Strongly endemic ♦ Endemic ♦ Sporadic cases

In 2000, typhoid fever caused an estimated 21.7 million illnesses and 217,000 deaths.[42] It occurs most often in children and young adults between 5 and 19 years old.[43] In 2013, it resulted in about 161,000 deaths – down from 181,000 in 1990.[13] Infants, children, and adolescents in south-central and Southeast Asia experience the greatest burden of illness.[44] Outbreaks of typhoid fever are also frequently reported from sub-Saharan Africa and countries in Southeast Asia.[45][46][47] Historically, before the antibiotic era, the case fatality rate of typhoid fever was 10–20%. Today, with prompt treatment, it is less than 1%.[48] However, about 3–5% of individuals who are infected develop a chronic infection in the gall bladder.[49] Since S. e. subsp. enterica is human-restricted, these chronic carriers become the crucial reservoir, which can persist for decades for further spread of the disease, further complicating the identification and treatment of the disease.[50] Lately, the study of S. e. subsp. enterica associated with a large outbreak and a carrier at the genome level provides new insights into the pathogenesis of the pathogen.[51][52]

In industrialized nations, water sanitation and food handling improvements have reduced the number of cases.[53] Developing nations, such as those found in parts of Asia and Africa, have the highest rates of typhoid fever. These areas have a lack of access to clean water, proper sanitation systems, and proper health-care facilities. For these areas, such access to basic public-health needs is not in the near future.[54]

Ancient Greece

In 430 BC, a plague, which some believe to have been typhoid fever, killed one-third of the population of Athens, including their leader Pericles. Following this disaster, the balance of power shifted from Athens to Sparta, ending the Golden Age of Pericles that had marked Athenian dominance in the Greek ancient world. The ancient historian Thucydides also contracted the disease, but he survived to write about the plague. His writings are the primary source of information on this outbreak, and modern academics and medical scientists consider typhoid fever the most likely cause. In 2006, a study detected DNA sequences similar to those of the bacterium responsible for typhoid fever in dental pulp extracted from a burial pit dated to the time of the outbreak.[55]

The cause of the plague has long been disputed and other scientists have disputed the findings, citing serious methodologic flaws in the dental pulp-derived DNA study.[56] The disease is most commonly transmitted through poor hygiene habits and public sanitation conditions; during the period in question related to Athens above, the whole population of Attica was besieged within the Long Walls and lived in tents.

16th and 17th centuries

Some historians believe that the English colony of Jamestown, Virginia, died out from typhoid. Typhoid fever killed more than 6,000 settlers in the New World between 1607 and 1624.[60]

Nineteenth century

A long-held belief is that 9th US President William Henry Harrison died of pneumonia, but recent studies suggest he likely died from typhoid.

During the American Civil War, 81,360 Union soldiers died of typhoid or dysentery, far more than died of battle wounds.[63] In the late 19th century, the typhoid fever mortality rate in Chicago averaged 65 per 100,000 people a year. The worst year was 1891, when the typhoid death rate was 174 per 100,000 people.[64]

During the Spanish–American War, American troops were exposed to typhoid fever in stateside training camps and overseas, largely due to inadequate sanitation systems. The Surgeon General of the Army, George Miller Sternberg, suggested that the War Department create a Typhoid Fever Board. Major Walter Reed, Edward O. Shakespeare, and Victor C. Vaughan were appointed August 18, 1898, with Reed being designated the president of the board. The Typhoid Board determined that during the war, more soldiers died from this disease than from yellow fever or from battle wounds. The board promoted sanitary measures including latrine policy, disinfection, camp relocation, and water sterilization, but by far the most successful antityphoid method was vaccination, which became compulsory in June 1911 for all federal troops.[65]

Twentieth century

Mary Mallon ("Typhoid Mary") in a hospital bed (foreground): She was forcibly quarantined as a carrier of typhoid fever in 1907 for three years and then again from 1915 until her death in 1938.

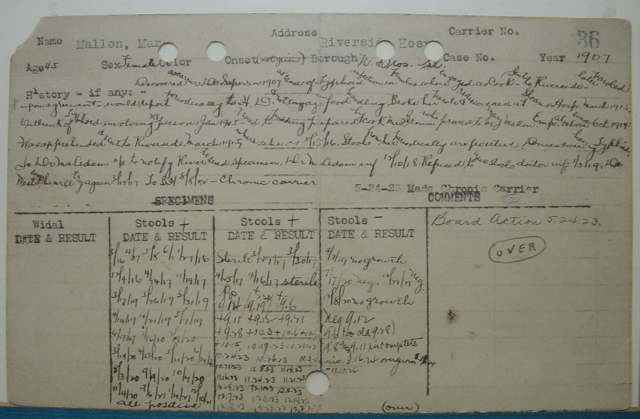

Original stool report for Mary Mallon, 1907.

The most notorious carrier of typhoid fever, but by no means the most destructive, was Mary Mallon, also known as Typhoid Mary. In 1907, she became the first carrier in the United States to be identified and traced. She was a cook in New York, who was closely associated with 53 cases and three deaths.[68] Public-health authorities told Mary to give up working as a cook or have her gall bladder removed, as she had a chronic infection that kept her active as a carrier of the disease. Mary quit her job, but returned later under a false name. She was detained and quarantined after another typhoid outbreak. She died of pneumonia after 26 years in quarantine.

A notable outbreak occurred in Aberdeen, Scotland, in 1964, due to contaminated tinned meat sold at the city's branch of the William Low chain of stores. No fatalities resulted.

Twenty-first century

In 2004–05 an outbreak in the Democratic Republic of Congo resulted in more than 42,000 cases and 214 deaths.[43]

History

Spread

During the course of treatment of a typhoid outbreak in a local village in 1838, English country doctor William Budd realised the "poisons" involved in infectious diseases multiplied in the intestines of the sick, were present in their excretions, and could be transmitted to the healthy through their consumption of contaminated water.[69] He proposed strict isolation or quarantine as a method for containing such outbreaks in the future.[70] The medical and scientific communities did not identify the role of microorganisms in infectious disease until the work of Robert Koch and Louis Pasteur.

Organism involved

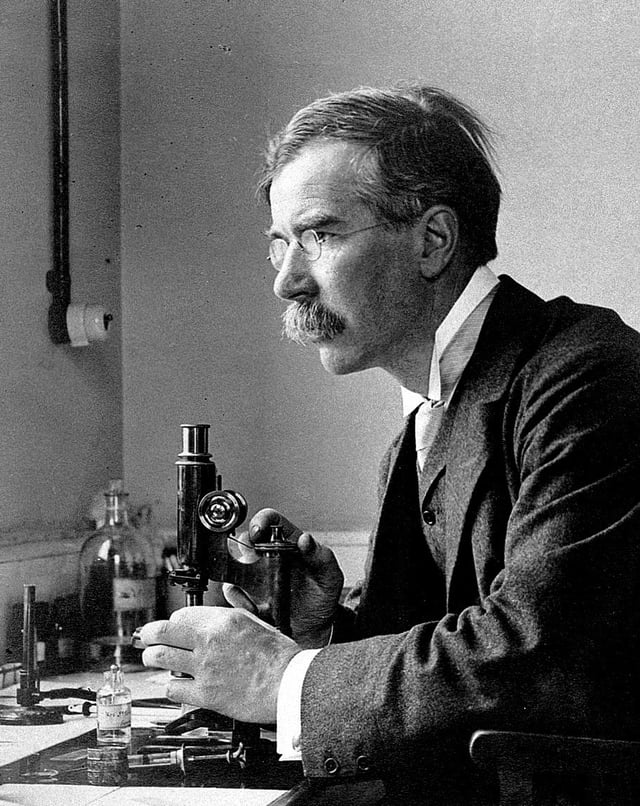

Almroth Edward Wright developed the first effective typhoid vaccine.

In 1880, Karl Joseph Eberth described a bacillus that he suspected was the cause of typhoid.[71][72][73] In 1884, pathologist Georg Theodor August Gaffky (1850–1918) confirmed Eberth's findings,[74] and the organism was given names such as Eberth's bacillus, Eberthella Typhi, and Gaffky-Eberth bacillus. Today, the bacillus that causes typhoid fever goes by the scientific name Salmonella enterica enterica, serovar Typhi.

Vaccine

British bacteriologist Almroth Edward Wright first developed an effective typhoid vaccine at the Army Medical School in Netley, Hampshire. It was introduced in 1896 and used successfully by the British during the Boer War in South Africa.[75] At that time, typhoid often killed more soldiers at war than were lost due to enemy combat. Wright further developed his vaccine at a newly opened research department at St Mary's Hospital Medical School in London from 1902, where he established a method for measuring protective substances (opsonin) in human blood.

Citing the example of the Second Boer War, during which many soldiers died from easily preventable diseases, Wright convinced the British Army that 10 million vaccine doses should be produced for the troops being sent to the Western Front, thereby saving up to half a million lives during World War I.[76] The British Army was the only combatant at the outbreak of the war to have its troops fully immunized against the bacterium. For the first time, their casualties due to combat exceeded those from disease.[77]

In 1909, Frederick F. Russell, a U.S. Army physician, adopted Wright's typhoid vaccine for use with the Army, and two years later, his vaccination program became the first in which an entire army was immunized. It eliminated typhoid as a significant cause of morbidity and mortality in the U.S. military.[78]

Chlorination of water

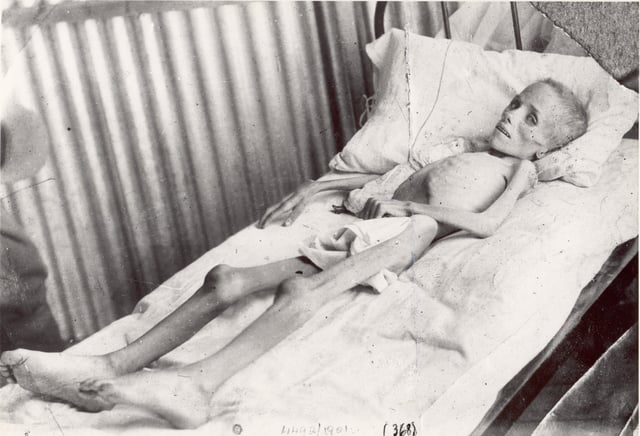

Lizzie van Zyl was a child inmate in a British-run concentration camp in South Africa who died from typhoid fever during the Boer War (1899–1902).

Most developed countries had declining rates of typhoid fever throughout the first half of the 20th century due to vaccinations and advances in public sanitation and hygiene. In 1893 attempts were made to chlorinate the water supply in Hamburg, Germany and in 1897 Maidstone, England was the first town to have its entire water supply chlorinated.[79] In 1905, following an outbreak of typhoid fever, the City of Lincoln, England instituted permanent water chlorination.[80] The first permanent disinfection of drinking water in the US was made in 1908 to the Jersey City, New Jersey, water supply. Credit for the decision to build the chlorination system has been given to John L. Leal.[81] The chlorination facility was designed by George W. Fuller.[82]

Antibiotics

In 1942, doctors introduced antibiotics in clinical practice, greatly reducing mortality. Today, the incidence of typhoid fever in developed countries is around five cases per million people per year.

Terminology

The disease has been referred to by various names, often associated with symptoms, such as gastric fever, enteric fever, abdominal typhus, infantile remittant fever, slow fever, nervous fever, and pythogenic fever.

Notable cases

William Henry Harrison, the 9th President of the United States of America, died 32 days into his term, in 1841. This is the shortest term served by a United States President.

Stephen A. Douglas, political opponent of Abraham Lincoln in 1858 and 1860, died of typhoid on June 3, 1861.

William Wallace Lincoln, the son of US president Abraham and Mary Todd Lincoln, died of typhoid in 1862.[83]

Edward VII of the UK, while still Prince of Wales, had a near fatal case of typhoid fever in 1871.[84] It was thought at the time that his father, the Prince Consort Albert, had also died of typhoid fever (in 1861)[85] but this is disputed.

Leland Stanford Jr., son of American tycoon and politician A. Leland Stanford and eponym of Leland Stanford Junior University, died of typhoid fever in 1884 at the age of 15.[86]

Gerard Manley Hopkins, English poet, died of typhoid fever in 1889.[87]

Lizzie van Zyl, South African child inmate of the Bloemfontein concentration camp during the Second Boer War, died of typhoid fever in 1901.

Dr HJH 'Tup' Scott, captain of the 1886 Australian cricket team that toured England, died of typhoid in 1910.[88]

Arnold Bennett, English novelist, died in 1932 of typhoid, two months after drinking a glass of water in a Paris hotel to prove it was safe.[89]

Hakaru Hashimoto, Japanese medical scientist, died of typhoid fever in 1934.[90]

Lourdes Van-Dúnem, Angolan singer, died of typhoid in 2006.[91]

Heath Bell, a relief pitcher for the San Diego Padres, acquired typhoid on a 2010 trip to Fiji, and survived.[92]

See also

Jarisch-Herxheimer reaction

Kauffman–White classification